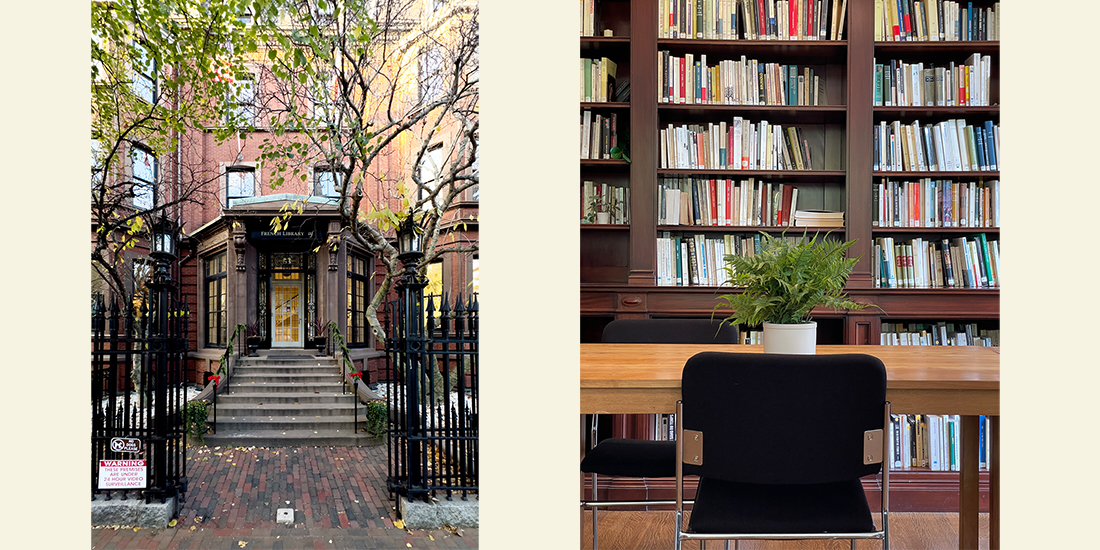

For a French Library, there’s a lot of American history to be found within the rooms of this stately Boston building. Before its current iteration, 53 Marlborough Street housed some of Boston’s greats: wine merchants, museum curators, and sculptors. Built in 1867, the house was designed in the French Academic style by one of Boston’s most famous architects, Charles Brigham (foreshadowing maybe?). Over the course of 100 years, the house was home to wine merchant Edward Codman and his family, then Gardiner Martin Lane, president of the Museum of Fine Arts in the early 1900s. Lane’s daughter, Katherine Lane Weems, an accomplished sculptor, later took over the illustrious abode. You may recognize her bronze rhinoceroses at Harvard University’s Biological Laboratories, or the group of playful Dolphins at the New England Aquarium.

Luckily for Boston’s Alliance Française, the Lane’s were reportedly Francophiles and took French language lessons on the third floor of their home. Thus, in a deed in 1961, Katharine Weems donated the house to the French Library, specifying that the house was to be used only for the purposes of the French Library and could not be sold.

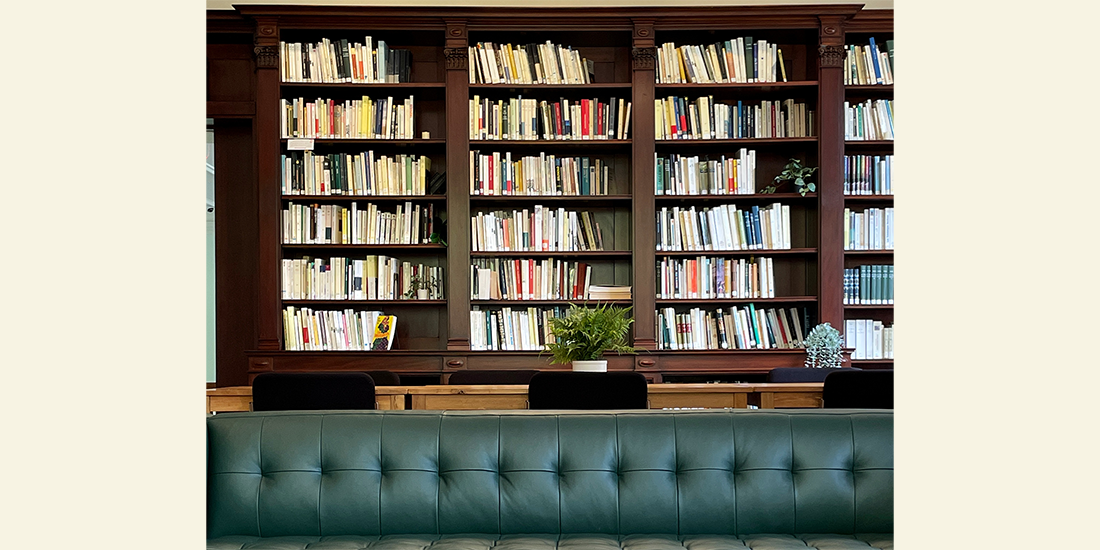

Over 60 years later the house remains home to the French Library with the addition of 300 Berkeley next door, also built in 1867. The French Library is an independent, non-profit organization dedicated to language and cultural education in Boston and Cambridge. Under these two roofs is the largest private collection of French books and materials available in the United States.

Work was recently done to make the connection of the two structures a little easier than going out one back door to the other (Boston winters are trying). J.L. Dunn was brought in for the work and had three main goals for the renovation of the French Library: create a seamless integration of the two independent structures, make the new building complex ADA accessible, and preserve the building’s history and architectural details. What stands as the greatest testament to the team’s attention to detail and dedication to historic preservation is the grand staircase. Restored and extended, the group spent countless months replicating the original staircase, even hand milling fabricating elements off-site so that even Charles Brigham could recognize it. The necessary installation of an elevator and other accessibility interventions were done thoughtfully, so as to not disrupt the historic charm of the building. A new sprinkler system was sensitively integrated, and the installation of a new groundwater recharge system left two magnolia trees, planted in the year of the French Library’s founding, unharmed.

/ 2

The French Library project demonstrates that it’s possible to enjoy the benefits of both worlds: maintaining a code-compliant, modernized building while preserving its historical essence. The team remained unwaveringly true and sensitive to the original architectural details while making the building and the library’s programming more accessible to the community.

“Too often it is assumed that old buildings cannot be energy efficient, accessible, and safe, or that extensive sacrifices to historic fabric must be made to facilitate these upgrades,” says Alison Frazee, Executive Director of the Boston Preservation Alliance. “The French Library team proved that old buildings can continue to serve their communities for generations to come with thoughtful, sensitive interventions.” Beautifully integrating the old and the new? Très magnifique.