From hand sketching to digital rendering, the tools available to architects have made significant leaps in the past few decades. How have additional tools such as 3D renderings, 3D Printers and even virtual reality played a roll in increasing creative solutions, and where do the tools of the past still come in handy? We’ll chat with DLR Group Principal and Design Leader Beau Johnson.

1. When you started out your career in architecture, what tools were available to you?

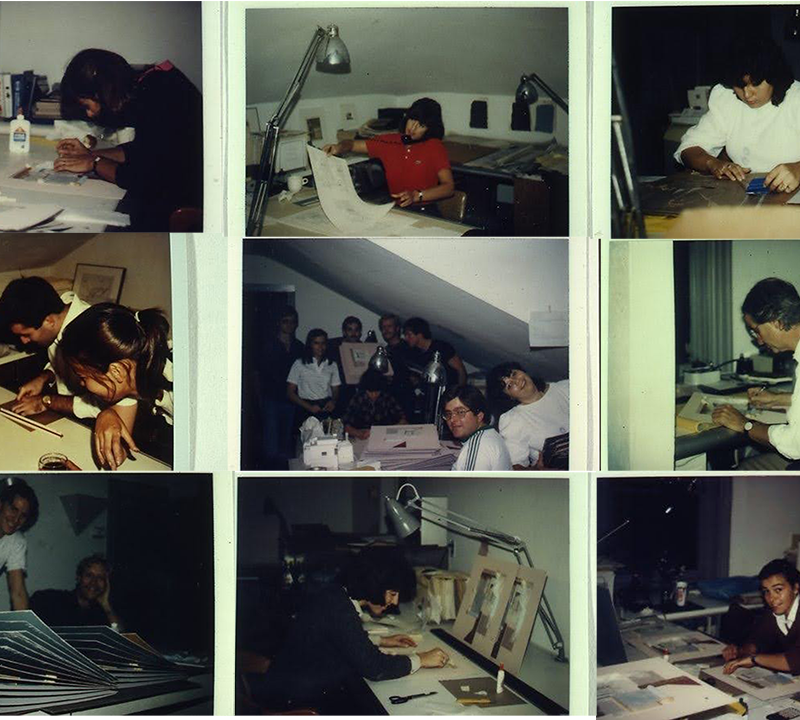

I often joke with our younger staff… “when I was in school, they started teaching us this new digital software called ‘Photoshop’…” So, that will slightly date me. But in all seriousness, I came into the world of architecture – both academically and professionally – at a time of transition. In school, I used a parallel-rule bar learning technical hand-drafting skills and made digital collage-type renderings in Adobe. At my very first internship, I learned how to use a blue-print machine.

Academically, I studied at Iowa State University and Rhode Island School of Design, two programs that truly value the physical tactility of design and architecture, so we made a lot of models, creating drawings with a wide variety of mediums, and were never prescribed a particular ‘tool’ for exploration or graphic representation. And that really transitioned into my early professional experience as well. We made models regularly – both “sketch” models (process) to presentation models – because often, even still, the model is the most effective way to communicate with clients.

2. In what ways do you still find hand sketching and traditional architectural methods valuable in your design process?

For me personally, I need to draw – to think. Sketching by hand is an extension of my mental, creative process. Once I draw something on paper, I’m able to think more critically about it and I get into this mental and physical rhythm where ideas evolve. Throughout my career, I’ve found that if I don’t start drawing, my brain does not fire in the same way. It’s really not technical either, it’s just a pen or pencil… in a sketchbook, on a roll of trace paper, or just the margins of an existing drawing. It’s iterative, sketchy, continuously testing ideas. Drawing also allows me the flexibility to look objectively, from all angles and at all scales.

3. Have you ever found it difficult to adapt to any of the new technologies available for architectural planning?

I wouldn’t say I’ve found it difficult, per se, because I think all the new technologies offer a varied perspective or evolve a certain opportunity in our pression- and I’m all for challenge and improving our way of practice. I’m always up to try something new, but I’ll say that I’m quick to understand which tools work for me and accept that some do not. In that case, I’m keen to surround myself with talented collaborators who are far more technically skilled than myself.

It’s interesting… having taught at the University level for about 5 years now, and worked with the young professionals in our offices, the students coming out into the profession now, they “think” with the computer – in the same way I think with a pen in my hand. If I ask them to hand-sketch me something they look at me somewhat dumbfounded – the same way I’d look if they ask me to script something in Grasshopper.

4. Can you share an experience where new technologies were particularly helpful in communicating your design intention?

Over the past few years, we’ve created an increasing number of video animations that have been highly successful in our story-telling. In some ways it’s basic – the moving image offers you so much more depth of understanding than the still. But it goes beyond that, we’re able to visually articulate volume and space more clearly through a moving image and be highly specific in targeting the audience.

Today, there are dozens of rendering softwares that can effortlessly create ‘fly-through’ animations, where you can control daylight, season, you name it. Combine that within an editing platform (like Adobe Premier + Suite), utilize some animated graphics if applicable, overlay music or voice-overs, and you can create some pretty powerful storytelling.

5. On the contrary – Can you share a story where an old-school tool or method unexpectedly solved a problem that modern technology couldn’t?

As mentioned previously… I’ve never found a client or audience that didn’t appreciate a physical model.

Often, when we’re starting a collaborative project with a client and we’re looking for their feedback, we’ll begin with simple, physical blocks. Together, we’ll move the pieces about the model, because everyone understands a physical model. It’s approachable. It’s accessible to everyone. When the content is on the screen or in the computer, we (and our audience) are always ‘on the outside’; we’re not able to interact with it in the same way. I can think of a handful of really successful projects that started, collectively, around a table and some colored blocks.

6. Do you think the reliance on digital tools has affected the way architects are trained or their creative processes? If so, how?

Yes ! – as mentioned previously – I see it in my students and the young professionals in our office. They think with through the computer, through digital 3D modeling. In the same way that I think through sketching with a pen. But I don’t see that as a negative, simply a difference. They see, iterate and think creatively in a different way – and I think those divergents are healthy for our collective process.

I would say, my critique is not their way of thinking or using the tool, it’s that commonly the computer their only tool. They spend so much time training in the many digital technologies that have come into the profession, that they’re far less skilled in other forms of creative thinking – the physical tools, like sketching, painting, drafting and/or model making.

7. Are there any technologies on the horizon that you’re particularly excited about?

Obviously, over the past year or so, AI has come to the forefront of all discussions on content creation, representation, and our creative processes – across all facets of our society. It’s certainly powerful in its potential. And while many are concerned, I’m quite optimistic as to how we can apply machine learning to our practice. I see it as another tool that we can program, integrate, and utilize to improve our output. At DLR Group, our designers are working with our design technologies team to find creative and safe applications for AI through our firm.

8. Are there any traditional tools or methods you think will never be fully replaced by digital alternatives? Why?

That’s a tough one, it kind of depends how far down the rabbit hole you want to go…. I mean assuming we’re still physical beings, occupying this physical space together, I think the physical model will forever have a place and remain one of the most effective ways to communicate architectural and spatial ideas.

That said, I think the tools that survive serve a purpose and have not yet been made obsolete by a different tool. As we continue to work globally, the way we communicate must become virtual; it already has. But even through we’re now collaborating on a web-based “white-board”, as opposed to the physical one at the end of the conference room, there’s still a pen tool, where you can sketch out your half-baked idea and your team can see it, and comment on it, and iterate on it, in real time; no matter where or what room they’re sitting in. So, while the “paper” may have changed or the tools have evolved (and will likely continue to), I don’t think the methods – of drawing and modelling – will ever truly be replaced.